Sharing this post on social media? Use this description to make it accessible: [Image description: Illustration from ‘Gaijin, American Prisoner of War,’ by Matt Faulkner. A white police officer fills most of the image pointing an accusatory finger at a Japanese American man and teen, “…says I gotta let you two go. But I’m gonna keep my eye on you, so you keep your noses clean. Got it?” The older Japanese American man, diminutive and passive in the background, looking worried, responds “Yes, sir.” The teen is still, quiet, with a wounded look on his face.]

What is the impact when our schools focus on one singular event of anti-Asian racism to unpack stereotypes about yellow peril and the foreign menace within the US? How do we talk about the way we imprisonment our own citizens for the crime of Asian heritage? What impact has that had in refusing to learn from the past?

And what are we teaching our next generation – when every story we reach about Asians in the US portray us as victims and side-kicks, never heroes or the drivers of our liberation?

The way we talk about our atrocities determines how we empower our next generation of Asian American leaders

January 30th is Fred Korematsu Day! Which seems to be the one day each year when a small fraction of the US acknowledges that anti-Asian racism might still be a thing. Or that racism against Asians ever existed at all.

We’re still far from acknowledging that anti-Asian racism is persistent, contemporary problem. We like to pretend that racism, violence, and discrimination against Asians in the US over, because we have so many ‘good’ stereotypes about Asians as model minorities. With the rare exception of Lee & Low publishers (an Asian-founded org), publishers won’t touch anti-Asian racism unless we’re reading about something concrete, clear-cut, and (to hear non-Asians talk about it), over.

Unless, of course, we’re talking about food.

We want to believe that the bamboo ceiling is a myth – conveniently cherry-picking stats about East Asian men making more money than White men. We forget how many (particularly 1st generation immigrants, Black & brown, Muslim, colonized, women & multiply-targeted) Asians are discriminated against for employment and housing, booted off planes, harassed on the street, beaten, imprisoned, and killed on perceptions of being an outsider, the perpetual foreigner.

We’re uncomfortable speaking up about how us Asians are often complicit in white supremacy, many of us fomenting and profiting off racial divides and oppression against Black, Indigenous, and Latinx folks. We forget that that many of our narratives and power amplify the voices of East Asians, distributed through a filter of colorism against our own – Western, Southern, and rural Asians – not to mention doubling-down dismissing and excluding multiracial Blasians from our history and our affinity spaces. Silent about the impact of the severe human trafficking, abuse, and exploitation – a problem that disproportionately affects South Asian women and drives the adoption industrial complex.

I’ve seen too many of us step on others shouting about ‘bootstraps’ instead of fighting for equality together. No one wins in all this infighting and exceptionalism.

Raising Luminaries is free and accessible for readers who can’t afford a paywall. Posts may contain affiliate links, which allow me to earn a commission at no extra cost to you. Check out the full affiliate disclosure along with my statement of accountability. If you’re into supporting libraries (please do!) more than consumerism, you can also support my work directly:

Donate or shop using an affiliate link via| Paypal | Venmo | Ko-fi | Buy a t-shirt | Buy a book

How we perpetuate harmful messages about victim-blaming, compliance, and whitewashing in kidlit

Ideally, we’d focus on stories about, and written by non-East Asians. For now, let’s take advanage of this ONE of increased google searches, when folks actually pay attention to anti-Asian racism within the US.

This Fred Korematsu day, let’s take a gander at the experience of Japanese Americans imprisoned in their own country, and how we perpetuate stereotypes and racism against Asians through the lessons we teach our kids today. And then – how we use imperfect tools to talk with children about anti-Asian racism as A Thing That Still Needs Fighting

Transparency: As a non-Japanese Asian American, I’m sure I’ll miss some stuff, so Japanese friends – feel free to add the stuff I’m missing in the comments.

We don’t have many books about anti-Chinese racism in the US (even though, as we’ve learned through the 2020 pandemic, it’s still alive and well!) From a sample size of Paper Son and a few bland books written by white folks in the 90’s, there just aren’t enough books to discuss within in my lane as a Chinese American to unpack anti-Asian racism. We don’t have a Mabel Ping-Hua Lee or Grace Lee Boggs day (yet!) to inspire school curriculum or drive publishers to fill that gap.

So I’m gonna swerve out of my lane to unpack how we use books on Asian American history in our homes and schools. We’re gonna amplify #OwnVoices Japanese American authors in these stories – and compare how differently these stories are told when appropriated by white & non-Japanese authors.

How bad can it really get if we let white folks control the narrative on 80-year-old history?

Pretty bad, actually. Whitewashing isn’t just an issue of being offensive. The practice of folks with lived experience appropriating these stories is actively dangerous – shaping the narrative not just on history – but on the decisions we make moving forward.

We have made some really, really horrible mistakes recently – and that’s due in part to how we failed to learn from the atrocity of imprisoning Japanese Americans on their home soil. Let’s examine how the way we talked about this violence succeeded – and the many ways we failed.

#OwnVoices Books about Japanese Internment

We read The Bracelet, Fish For Jimmy, and A Place Where Sunflowers Grow to introduce the history of US internment of Japanese Americans. All of them engage kids through the lens of a child protagonist, and don’t choke kids with facts, dates, and name-dropping. Just experiences and emotions.

The Bracelet is a firm #OwnVoices story – based on the experiences of the author’s childhood. The recommended age is for 4-8, but honestly? The themes and quiet message in the book goes way over your average preschooler’s head, and I’d save it for the 6-9 crowd. In this story, we see the way Uchida’s white friend loves and cares for her, but ultimately can’t do much to protect her from systemic injustice. Due to ancesry, and that alone, Uchida will go on to have a much more challenging life than her white peers.

![]()

Fish For Jimmy is a follow-up generation #OwnVoices story, based on the author’s family history as retold by her elders. It’s great for 6-9, although we were able to paraphrase and rely on the images for the 4.5-year-old, and he caught the gist. Maybe it’s because the Earthquakes are so invested in their relationship as brothers – but this one hit home in the way a Uchida’s subtle story about a friendship bracelet didn’t.

![]()

A Place Where Sunflowers Grow is also a follow-up generation #OwnVoices, based on the authors family story. As a grownup, I found this story to be the most engaging, the illustrations gorgeous. Unfortunately, the muted colors didn’t pull the Earthquakes in and it took some wrestling to get them to sit down and read it with me.

I also made the mistake of trying to read the preface aloud. Don’t do what I did!

Between the dusty illustrations and a dry preface, my kids got antsy. So just jump into the story, which did engage the 6-year-old. In terms of gorgeous, timeless literature, this is one of those books that belongs on every family & classroom bookshelf. But it also requires time and attention to really wrestle with the story of frustration, endurance, institutional racism, militarism, and endurance. This isn’t a quick library read. Bonus points, it’s also bilingual, written in both Japanese and English.

So what happened to Americans after they left the camps?

Here’s where we start to notice some sneaky gaps in representation.

For kids who want to delve deeper into the long-term impact of Americans imprisoned in the internment camps, either they’ll have to wait until they’re much older, or they’re gonna have to rely on re-tellings by non-Japanese authors.

I mean, I’m sure there are plenty of Japanese American authors who could tell these stories. But until recently, it was only white folks who get publishing deals and promotions (more on that below.)

If younger kids want a glimpse into the longer-term impact, the best book we’ve found so far is Ruth Asawa: A Sculpting Life. Which is a great book ! But here’s a bit of clear and ridiculous example of racial gatekeeping – both this and A Life Made By Hand* are stories about a Japanese American artist written, and illustrated by non-Japanese makers. Like I get that white folks get a spark of inspiration and want to write about women of color. But like, can’t a publisher be bothered to poke around a bit to find one of the thousands upon thousands of talented Japanese American illustrators looking for work?!

Anyhoo – both the 5 & 7 year-olds enjoyed it for 1-2 reads, but no more. The story was engaging, and touches on the long-term impact of trying to find employment as a Japanese American artist in America…

…but the illustrations were dry and dreary. I do wonder if an illustrator with #OwnVoices Japanese American influence would have enticed them to come back for more.

*A Life Made By Hand (Not pictured) is an even more whitewashed, less interesting Asawa bio. The author doesn’t even mention the formative event of being imprisoned as a child and how it might have impacted her life work of making art that looks like cages. At least – not until the end notes for adults. Because we know this book was written for white kids, and nothing is more important than protecting a white child’s obliviousness (/sarcasm.)

Let’s move on to the glorious Gyo Fujikawa, our literary firebrand who broke through the white barrier of children’s literature.

Gyo destroyed bamboo ceilings back in the 50’s, and it’s not until 2019 (that’s like 70 years, COME ON!) that she’s recognized in the medium of her fame – with a biography written by my crush, Kyo Maclear

Began With A Page: How Gyo Fujikawa Drew The Way is an #OwnVoices story written by Maclear, a Japanese Canadian author – who you already know I have deep feelings for thanks to her book on growing up multiracial, Spork.

But a white illustrator – WHY. WHY?!

Wait, first – let’s clear up a common misunderstanding for books published by big kidlit. It’s usually the publishers who choose the illustrators, not the authors. I do hold white authors responsible for advocating for and potentially missing out on opportunities in order to be accomplices and advocate for illustrators of color – refuse to publish! Use your the shield of your whiteness!

But it’s hard enough to get published as a woman of color in kidlit. It’s an even harder sell to get a publisher to boost an Asian woman’s biography. (Remember, it took 70-freaking-years to highlight the most significant Asian kidlit illustrator of all time!) So I’m not gonna fault Kyo for this, as the publisher would have shut her down if she had pushed for this. The choice to hire a white illustrator to draw the life of an Asian illustrator who had to fight tooth and nail to break into the industry is a solid ‘WHAT THE FUCK?’ that belongs squarely the publisher’s shoulders.

What kind of publisher is like “You know what we need to really pack a punch about this JAPANESE WOMAN WHO BROKE RACIAL BARRIERS IN KIDLIT?! We need the most sanitized whiteness of hipster kidlit possible. Instead of taking this opportunity to boost a woman of color, let’s just hand it to Morstad. She seems like a safe bet.”

I. Am. BAFFLED.

Okay, next – I’m not gonna let Kyo completely off the hook. The writing in It Began With A Page is recommended for ages 4-8, but it’s all date-time-location-fact-fact-fact, so you’re gonna have to fight to get anyone under 8 to sit through the text. It’s not gonna inspire kids to pull this down from the bookshelf or ask for a second read.

But more importantly, the illustrations – just sanitized, dead-eyed sad shadows of Fujikawa’s genius, sucked of joy and whimsy. How did we MISS THE POINT!?

Okay, I’ve got that off of my shoulders. Now on to the point of the book. Fujikawa took what she experienced being imprisoned for her ethnicity as a child, facing agonizingly frustrating bamboo ceilings and barriers due to her race and gender, and broke open kidlit representation in support of the civil rights movement so kids of all races could see themselves reflected as important and worthy.

I love Gyo, and I love Kyo. I wanted so hard to love Began With A Page, and I just wanted it to succeed so hard. The climax shows how Gyo was impacted by Japanese internment, but my kids won’t let me get that far, they grumble and wander away. But this book lives on my bookshelf anyway – because between this and The Queen of Physics, this is really all we have for our young Asian daughters to show them it might be worth trying… anything.

Here’s where I get antsy for my kids to grow up so we can read Takei’s genius together

They Called Us Enemy is a solid #Ownvoices graphic novel, written my honorary internet grampa, George Takei.

First off, you should know that growing up Asian American, you’re required by law to love George, because like Fujikawa, he offered a reflection for Asian Americans in popular media that were rare and precious. But I’m gonna set aside my love for him for a moment to tell you that this is just genuinely a great book. You can trust me, cause I just endangered any possible future love affair with Maclear by bashing her book just now. (I STILL LOVE YOU, KYO. CALL ME SO WE CAN GROW OLD MAKING UNECESSARY LISZTS TOGETHER.)

So when I tell you this is the kind of book you must read before you die, I mean it.

Second, let me say that there is a solid correlation between celebrities who write children’s books and how shitty these books turn out, but Takei rocked this so hard. This story is one of the few books that includes white accomplices for Asians in a way that doesn’t center whiteness and saviorism. Does he ever do anything poorly? Damn! Can’t match this.

They Called Us Enemy is graphic novel excellence on xenophobia, racism, and the impacts of childhood trauma. Unfortunately it’s made for teens and adults, so it technically doesn’t belong here. No amount of paraphrasing and begging got my 7-year-old to sit still for it. At 8, he really wanted to read it, but the name dropping and politics was just way too much for him.

BOOGERS! Patience is not my virtue, but alas, we’re gonna have to wait.

Japanese Activists

So we’ve covered the stories of kids while imprisoned, and the impact of that trauma on the lives of path-makers after – but there aren’t many stories about Japanese Americans and Canadians who took action to hold governments accountable or prevent this from happening to people of color in the US ever again.

Fred Korematsu Speaks Up, written by Stan Yogi (whose parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles were all imprisoned) and Laura Atkins (whom I perceive as white) and illustrated by Yataka Houlette (no bios on the internet, but he’s obvs Asian and has a Japanese name) is an #OwnVoices story celebrating Asian rights activist Fred Korematsu, one of the few Asian Americans who actually has a US day designated in his honor.

Honestly – are there others? I can’t even think of any. He might be the only one. We don’t even get the Lunar New Year off from school, so let’s not act surprised.

And because it’s only one of like…four(?)* children’s books about Korematsu, and the only one that’s engaging enough to read – Fred Korematsu Speaks Up is another graphic novel that I kinda squeezed in before the recommended age. We were able to summarize the text and use the illustrations with the 5-year-old, and it held up! But it would still be a much easier read for an 8-year-old.

*4 is not a lot of biographies in the churn & burn kidlit industry. To give you some context: there are dozens (hundreds? I lost count) of biographies on anti-disability-rights, totes-cool-with-systemic-racism, Tom Brady. And he didn’t have to wait SEVENTY YEARS for his industry to acknowledge him.

Each chapter has a simple story, followed by facts, figures & photos from history about the theme of the chapter. The first chapter was about racial discrimination in a barber shop, followed by details on discrimination against Black, Chinese, and Irish Americans. Which might have hooked my Chinese-Irish kids in a bit deeper than most, as we can connect Fred’s activism to our own family history.

About halfway through the hook, they start talking about court rulings and lawyers, which is basically kidlit death (I’m old! Even I don’t have the patience to read legislation!) but the first half of the book gave us plenty to work with and talk about.

Note to kidlit authors – STOP NAME-DROPPING PEOPLE, PLACES, DATES, AND BORING SHIT. All dates between the extinction of the dinosaurs and the year they were born are roughtly the same day. Fact-dropping to prove you researched accurately is not impressive, nor convincing for young readers. Kids don’t care about your bibliography diligence, they resent it!

If you’re gonna write books for kids, write cognitively-engaging books for kids – they are not just short adults!

Wait, what about Canada?

If those of us in the USA are the aggressively racist uncle who lies about immigrants stealing packages off our porch, Canada is our outdoorsy, polite and soft-spoken ‘I’m not racist, but…’ colonial sibling who does just as much racism, but feels a little bad about it.

Since 2016, I’ve heard enough “Fuck it, I’m moving to Canada where racism doesn’t exist and also where I can afford an epipen.” for a lifetime. I mean the epipen argument is legit, but nothing says “I have no knowledge of history or systemic racism” like pretending Canada is a post-racial sanctuary.

Anyhoo – down here in the states, we don’t have a ton of access to Canadian literature, but Naomi’s Tree is a nice head-cracker to sum up Canada’s part in Japanese internment, along with a truth and reconciliation process that is just so on-brand for our northern neighbors. Still racist – but at least they apologize!(?) Canada’s government is a bit less fragile and belly-aching about admitting when they pulled some nasty shit. There’s an element of humility and lots of talking, followed up with the typical colonist ‘Glad we had that talk, let’s resume life as normal.’

Naomi’s Tree is an #OwnVoices story of Kogawa’s kidnapping, internment, and returning home to a changed land. It’s a bit too poetic for younger readers, but I think you can manage it for the 7+ crowd.

What happens when white folks control the narrative on anti-Asian racism?

Onto the bestsellers, award-winners, and the books you’re most likely to find on (white) parenting blogs and in a school libraries! Books about Asians, written by white folks.

Why can’t we just be honest about this – racism still exists cause it’s a profitable economy. First, you steal a bunch of folks’ land and livelihoods. Then you exploit them for cheap labor and mine their cultural cache while banning them from celebrating their heritage.

Then you publish books about the injustice of it all, and sell them to other white folks who have feelings about their complicity – who need to release that tension and shame – but don’t want to do stuff to create societal change. Ka-ching! It’s horrific, financial genius. Yay for our economy that measures the healthy of society using the singular variable of profit to measure success, I guess.

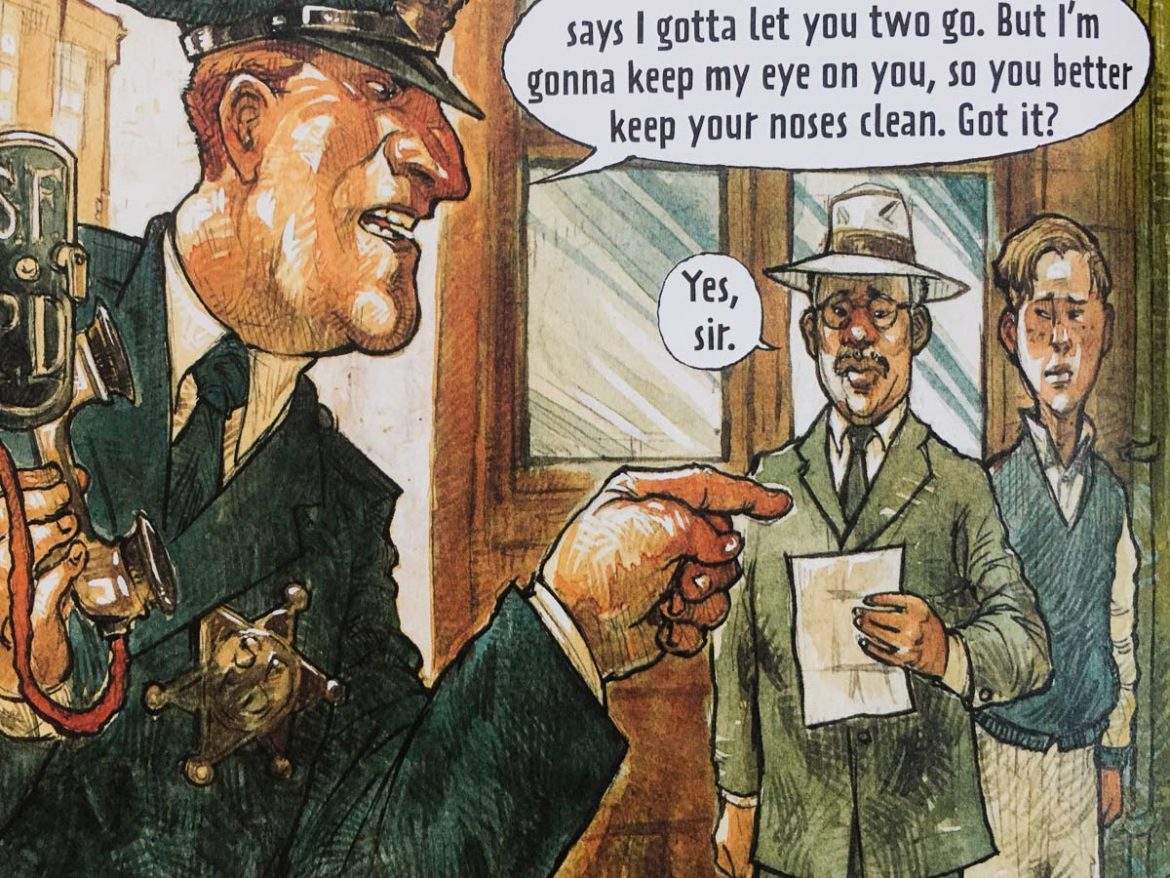

Let’s start with my guilty pleasure – Gaijin, Prisoner of War, which was inspired, but not BASED on the white author’s family history through (and this is really weak link) his Irish great-aunt who accompanied her Japanese kids to an internment camp. The author had never met this aunt, but going by the end-notes, he did at least make contact with Anita, one of his great-aunt’s great-granddaughters for some insight.

It’s interesting to note that Anita is not listed as a co-author or sensitivity reader for this story. I wonder if she’s getting a cut on a story inspired by her family trauma.

Okay, so let’s set that aside for a moment to say that stories are complicated! The 8-year-old and I loved reading this book! It was helpful to to unpack the issues my kid faces as a multiracial Asian American who may not be accepted by white folks or Asian folks in a society that only values distinct divisions. But it was also exhausting, because we had to stop every few moments to be like “Oh – but this here? That’s more of a white person thing.”

And that ending?

Where they all just kind of…got over the trauma of having their livelihood and homes ripped away, and being imprisoned?

The white author conveniently ignores the fallout of what happens after the camps were finally closed and families scrambled to find solid footing lost and broken homes, business, jobs, or communities?

Yeah. Don’t say you didn’t know how this was gonna end when you saw the cover.

You’ll notice this theme of no-long-term-damage in books written by white folks.

If what you’re looking for is a coming-of-age book for adolescent white boys wrestling with parent separation and peer-pressure from ne’er-do-well youths*, with a few nods to common multiracial microaggressions, and some gorgeous art – well here you are! This is an exciting hike about a tired over-used plot, laid against the decoration of historical fiction.

*The ne’er-do-well youths are illustrated with Japanese faces and are imprisoned in an internment camp – but code as flat, dimensionless white teens who show no signs of growing up with Japanese cultural values (not even as 2nd or 3rd generation immigrants). They have seemingly been abandoned by their Japanese parents, as they lack any adult oversight or family responsibilities. Unlike the kid with a gentle, pure, and hardworking white mom willing to sacrifice her freedom for her child! These yellow-faced white boys go through a that teenagery rebellion stage common to white kid teen movies. The message we’re expected to buy is that only the gaijin can resist the yellow peril of ruffneck peer pressure!

Reading this book is like waltzing barefoot in a room of legos. Those sharp jabs of whitewashing are a reminder – Oh, right! this white dude is profiting off real people’s trauma! While relying on the tired chestnut: ‘I’m an ally, ’cause my 4th cousin three-times-removed is Japanese.‘

We have the internet now. All those memes and microaggression bingo charts. White folks must know by now that’s no excuse!

Romanticizing a horrifying moment in our shared cultural history, and using it as a backdrop for a white boy’s story

Gaijin is an ironically perfec title. Koji, the Japanese American main character is culturally white. Slapping epicanthic fold on a white character doesn’t make him Asian. We’re decorating this white boy’s experience against the American exotic – without addressing the traumatic impact on those imprisoned (or their descendants) through the present day.

This reads like what it is – historical fiction about the multiracial Asian identity, as imagined by a monoracial white dude, for the gaze of white readers. I don’t know why I keep expecting better, and then still have to settle for…this. But I do! Because honestly, there just isn’t a lot out there to reflect the multiracial Asian identity. So we read these whitewashed stories to our kids to fill the vacuum, and do our best to discuss how clumsily it’s done.

Now let’s talk about white-passing privilege! (Which this book does not.)

You might notice from the cover – the biracial character, Koji has lots of white passing privilege. Far more than your average biracial Asian/European. Faulkner couldn’t even bring himself to draw Koji with dark hair, eyes, or even skin a shade darker than Northern Irish. I can almost hear his inner monologue on the character design – “If he looks like the actual multiracial cousins I’ve based him on – how will [white] people tell the difference? All Asians look the same!”

The only way this white illustrator could see Koji as a sympathetic multiracial character was to give him a classic white boy look, but squinch up the eyes a bit.

As Koji presents in the book, I find it hard to believe rando white strangers on the street would identify him as Japanese enough to make snap judgements and discriminate against him. Nothing in the story suggests he benefits from his white-passing privilege. What are the odds that this white author even knows that’s a thing?

Sure – there are blonde, light-eyed biracial white/Japanese kids who deserve representation. But this is not it. Koji was based on the story of Faulkner’s real actual cousins, who, like many kids handed dominant genes for darker coloring, had to deal with the colorism of darker hair, eyes, or skin, being perceived as an outsider first.

While lazy cartoonists have relied on eye shape to denote Asian phenotypes, that’s just not an actual thing that identifies or separate Asian & European ancestry! There are lots of white people who have epicanthic folds and lots of Asian people with double eyelids, but we rely on these ignorant assumptions about racial markers because it stereotyping saves us thinking power that we could save for choosing between which Tom Brady bio to donate to the school library.

This speaks to a common issue that kidlit illustrators fall back on – ‘what is a good way to help white people tell the difference between individual Asian people? How can we make push the boundaries on the Asian exotic for drama?…oooh! How about we draw them with attributes of whiteness, like light hair, freckles, and blue eyes?’

How DOES one draw the confusing, rare freakshow that is a biracial Asian person? I mean – we could hire actual multiracial models to create a realistic lens for under-represented people! But Nah. LET’S GIVE ‘EM SLANTY BLUE EYES!

Lazy.

If the moral of this story (which is more about toxic masculinity and peer pressure during those heady days of teenage angst) was set against a regular white kid life, it just would just be a tired, over-told story. It’s the wrapping – the borrowing of the multiracial Japanese identity that makes this book engaging. And as much as I did enjoy reading it – that is a systemic racial problem we really need to reckon with.

So here’s the biggest problem – Gaijin is accessible and engaging for younger readers, it validates and reflects the challenges of wealthy white boys – and it’s easier to reach for than books like Fred Korematsu Speaks Up and They Called Us Enemy. Because it’s lighter, and doesn’t touch on all that pesky trauma and complexity of what it means to be actually Japanese in a hostile home country – it’s easier to read this book, it’s easier buy this book, it’s easier to sell this book.

Why? Because Faulkner, a white man who didn’t have the weight of representing his entire race, was provided the freedom to add unrealistic drama and had the trust of the publishing industry behind him. Yogi & Takei have a lot riding on being as accurate and sensitive as possible, without wrapping up the books in a neat, white-innocence-protecting bow.

If a white guy messes this up, the worst he’ll get is a ranty review on an obscure website about kidlit. Easy to dismiss an Asian mom – they’re just getting hysterical and over-sensitive about kids books, right?

But if Japanese authors mess this up – they have to worry about all Japanese people being discounted, ignored, sidelined. Or worse – the targeting and criminalization of their families, an ever-present threat that could happen again.

Keeping the focus of Asian American history… on white women.

For a few years, I kept seeing Write To Me pop up in my search for books about Asian American history. Which is weird – ’cause it’s about… a white lady?

As is the case with all books celebrating a white person in a story that primarily affected people of color – the author is white. The illustrator, Amiko Hirao, was born in Japan and grew up moving back and forth between Japan and the US as a kid, I haven’t seen any mention of whether Hirao’s family was Japanese American during internment.

Non-Asian folks like to lump people of the Asian diaspora (including third-culture kids & immigrant families – folks who grew up fluent in two or more cultures) with all people of Asian descent – but that’s a dramatically different experience. Very different cultures, family history, and personal impact! Including a Japanese illustrator in this project does not automatically render it an #OwnVoices story. (Hirao might actually have family who experienced internment in the US, I just haven’t found evidence of it, and you’d think she’d mention it if so?)

For example – As an Irish American whose family came to the US during the Great Hunger (1840s), being Irish doesn’t mean I have any family connection or have to deal with the generational trauma of The Troubles in Ireland (1960’s-90’s). Our family missed that horror, completely unscathed and unaffected. So if someone invited me to come work on a project about the Troubles as the Token Irish – well, that’s a terrible pick for your token diversity hire.

Back to the author – in one interview, Grady goes into detail on her research, describing how she was “devastated” because another white woman had already celebrated this white savior.

(How is this still a thing? Most authors just don’t do basic internet searches for ‘Does the book I want to write already exist?’)

It can be a gut punch to realize you can’t get all the attention and kudos for a project that you’re excited about. But like – it’s also another reflection on the ego of whiteness – making the targeting of people of color so far removed from actual people of color that the story becomes about the white folks in the room. This was 2005 – and a decent book about Korematsu, or really any Japanese activist who didn’t rely on a white savior – still had to wait another 12 years to hit a bookshelf. Instead of swerving to highlight a Japanese activist, Grady doubled down and was like, NO! We need TWO books about white ladies to crowd up the library bookshelves on AsAm history!

Whatever, it’s fine. She’s a white lady, writing about white ladies – and that’s in her lane, no toes stepped on. It’s cool that Grady sought out primary documents for her story.* In her end notes, she placed weight on documents and museum historians by name (some of them Japanese), but not a single credit for an #OwnVoices survivor of the camps.

Maybe she did talk to a bunch of people who were impacted first-hand by internment (why not credit them as primary sources tho?) But it’s just kind of weird…no, actually, it’s very typical…to credential her work through worship of the written word and academic ‘experts’ (oh hai, education and class barriers to being believed about systemic discrimination!)

I’m just saying it’s a little weird that for a story on Japanese Internment, with so many articles by, on, and about the author’s process, we don’t hear any references to talking with actually interred Japanese people? It’s also telling that if you search for books on Asian American history, it’s usually white parents who are relying on a white savior’s story to introduce kids to the concept of anti-Asian racism.

*At least it’s not a Kathleen Krull ouroboros – regurgitating history using only other children’s books as sources. Quantity over quality, another great way to profit white folks using the stories of targeted people!

I don’t have to tell you this, because I’m sure you’ve already figured it out – the story itself really harps on the power of a white woman to heal the trauma of Japanese children targeted and imprisoned in unsanitary conditions. The story briefly alludes to the inhumanity (illness, insufficient food and bathroom facilities), just enough to make it seem like the experience was unpleasant, but not that bad. Just what we need – more ease for white kids to swallow while maintaining their white innocence/oblivion.

Maybe save it for your discussions on white accomplices – but this is not the story to rely on in schools (as it currently is) for teaching Japanese American history.

Celebrating performative allyship

A Scarf for Keiko is even cuter and more engaging than Write To Me, except the author manages to almost entirely remove Japanese people from the story of Japanese internment. Skills!

Malaspina, whom you all know I already have beef with thanks to books like Yasmin’s Hammer, has built her writing career on the noble victim trope and our celebration of performative allyship and saviorism. Kindred spirits, illustrator Liddiard, has a similar habit of centering the discomfort and feelings of abled folks who make a spectacle out of kids with limb disabilities.

Hold on, lemme take a few seconds to shake out my brain. These books just really frustrate me. And they’re like 90% of published mainstream books. The arrogance. The relentless flood of audacity.

I’m really not against books about accomplices! They are great for kids wrestling with privilege and show us how to get over ourselves in fighting for equality! It’s just… you know. The flood. Why do we have more books about white, abled, powerful accomplices, than we have #OwnVoices stories by people with lived experience? (Gatekeeping!)

::Deep breath::

This whole damn thing is about a white boy who has big feelings about convenient inaction, as he does nothing while the world crushes his friend Keiko’s soul. And when he does finally decide to stop being a cowardly little shit, he doesn’t ask her what support she needs. He just does what’s convient, pathetically late – and it’s really about appeasing his guilt more than actually helping her feel safe.

If you want to talk about how passive white silence still makes us an active participant in racism, then this is the book for that. Although – it’s gonna take a lot of work to connect this story in with how not okay the character’s behavior is. Cause the author either doesn’t even realize that white silence is a thing, or, maybe she just couldn’t be bothered to spell that out. Either way. Ugh.

Unless, of course, we’re assuming that a scarf from a former friend who betrayed us is gonna make Keiko feel any better.

We’ve all gotten those texts from white friends!

“Sorry I didn’t say anything when you were getting piled on! Now that it’s just the two of us and I face no risk of making other white folks dislike me, I’m totally here for you with platitudes!”

ABOLISH TOXIC FAUXSHIPS!

I’m not saying tokens of solidarity are worthless – The Bracelet already did this story, and did it much better, twenty-three-fucking-years earlier.

But, AUTHORS SERIOUSLY. Google is free! And it’s not even a bad idea to write another book abotu the same idea. But make sure it’s not a terrible version of the original.

Imprisoning Families could be wrong, could be right – there were Very Fine People On Both Sides …(?!!)

That’s sarcasm about the very fine people – in case you somehow missed that debacle. But I want you to read this book alongside the transcript of the American president throwing blame and compliments around willy-nilly between anti-racist protestors and nazis.

Pay attention to these echos. While settler American values have changed on the surface, the actual way our government runs – on fear and scapegoating – has not changed. Not since 1942. Not since 2009. Not since 2016.

So Far From The Sea, written by Eve Bunting, an author who habitually victim-blames Black people uprising against racial injustice, Indigenous children targeted by residential schools, and language barriers and ignorance for migrant poverty (and so on, I haven’t even read all of her books yet).

Just so many books about targeted people told through the blurry lens of the oppressor, under the guise of representation and awareness. (I do like some of her books – when she stays firmly in her lane and forgets to do a saviorism.)

This a solidly NOT #OwnVoices story. If you have zero insight on East Asian culture or history, and truly believe say, Korea and Japan are basically the same place and people (oh my gosh no), you’d think an Asian illustrator would balance it out. But no! According to his bio, Soenpiet is a Korean American (Korean born, trans-nationally adopted to American parents at 8) seems like a great token Asian illustrator to lend credibility to this book.

EXCEPT IT IS NOT! Oh my gosh, what was this publisher thinking?! While Soenpiet probably doesn’t hold any resentment toward folks with Japanese heritage (Japan being a country that colonized, targeted, and led to the death, displacement, and oppression of Koreans for decades, including a boom in transnational adoption) it’s just… it’s just such a terribly sloppy and weird choice for a Korean American to draw Japanese American characters so a white woman could spout shit like:

“Dad shrugs. ‘It wasn’t fair that Japan attached this country either. That was mean, too. There was a lot of anger then. A lot of fear. But it was more than thirty years ago, Laurie. We have to put it behind us and move on.’”

This story explaine how racism against American citizens is not just something the survivors should get over, but that this violence was justified because people from another fucking country also did a mean thing!

Bunting neglects to realize that in attacking Pearl Harbor as an attack on America – the Japanese government was also attacking Japanese Americans – because they, too, are American. With that one transparent line, we’re sold the same bullshit the American government sold us in the 40’s – that your ethnicity links you to the atrocities of a foreign government, not your citizenship, your community, or the culture you’ve grown up in.

Of course, that’s not all.

“‘It was wrong,’ I whisper. ‘Wrong. Wrong.’

‘Sometimes in the end there is no right or wrong,’ Dad says. “It is just a thing that happened long years ago. A thing that cannot be changed.”’

NO, YOU FUCKING ASS HAT. SOME THINGS ARE UNAMBIGIOUSLY FUCKING WRONG.

Imprisoning families! Yanking our own citizens from their homes and the businesses that took generations to build! Plopping them in unsanitary horse stables surrounded by barbed wire, toddlrs under constant watch of armed white dudes, stranding people in the fucking desert without enough food, clean water, or shelter! Stranding 127,000 American citizens in a constant state of ‘Is my own government about to kill my children?’

All of that is, unabashedly, completely WRONG, and for anyone who says it is – holy shit, check that fucker’s basement for folks they kidnapped for looking suspicious.

No, we can’t erase or undo history – but that doesn’t mean we excuse it. We don’t dismiss folks who, upon hearing the sanctioned atrocities of a democratic nation, say “Wow that was wrong.”

“Eh, you kinda deserved it!” is not the correct response to folks processing the facts of traumatic events.

In this story, a magically-recovered Japanese American family visits a monument where the parents were incarcerated. The monument is supposed to stand for a history that over. Bunting really rams it into the reader (through the yellow-face of her characters) that Japanese folks should just get over it.

Even just calling it wrong is too much – white folks gotta have the last word on everything.

Using the yellowface of these characters, in a children’s book where kids see the illustrations, not the author, Bunting implies there were no long-term ramifications, no elders generations still facing the trauma, no younger generations raised by parents struggling with trauma, no generations still working to overcome lost wealth, mobility, and dignity. No people of color worried that our government could get back to the same old shenanigans again.

As if all we need to live in a post-xenophobia post-racial society is for Asian folks to shrug it off and keep plowing ahead. Funny how the work of reconciling racial injustice must always fall on people of color, never on those in power to make amends.

We never learned our lesson. So what can we do moving forward?

In 2018 white folks were shook when 45’s administration separated families and left children in cages to die.

I mean seriously? How did you not see this coming?

Imprisoned children in cages, tortured families, a system built on enslavement and trafficking – our country has always been less concerned with caring about – and more interested in scapegoating and exploiting the tired, poor, and huddled masses – both within our citizenry and incoming. As we deport undocumented neighbors and community members – even through the 2020 pandemic, how are we surprised that this is still happening – when it never really stopped?

In November 2016, the weeks after the presidential elections, our family rushed to get passports. We were now under the rule of an openly white supremacist administration – one that was not only eager for a fight with China, but full of white men who would never bother to discern the difference between Chinese government officials and Americans of Chinese descent who had never stepped foot in the country.

My white partner thought I was being ridiculous. The US would never imprison families again. It was hard to justify the cost of four passports, when we can’t even swing a vacation within our own state, never-mind and international trip to Canada! Even if our government decided to imprison me as a Chinese American – weren’t our kids white enough to slip under the radar? Was I being too dramatic?

The atrocities of our past – and how accepting we are of them – shows us that racism will, eventually come for us – and these atrocities didn’t care how American we are. For four years, we kept those passports, and our go-bags, ready.

Tragically, I was not overracting at all. Despite the threats, and the looming apparition of war – our administration didn’t come for us. Instead, 45s administration targeted Latinx migrants – the people who run our farms and keep us fed. The people fleeing violence our country created in their home nations. We targeted them in uniquely cruel, horrifying ways. And nothing about that is shocking if you know how we still whitewash, excuse, and pretend we can’t be sure if ethnic discrimination and incarceration is wrong.

We don’t have to – we must refuse to accept this.

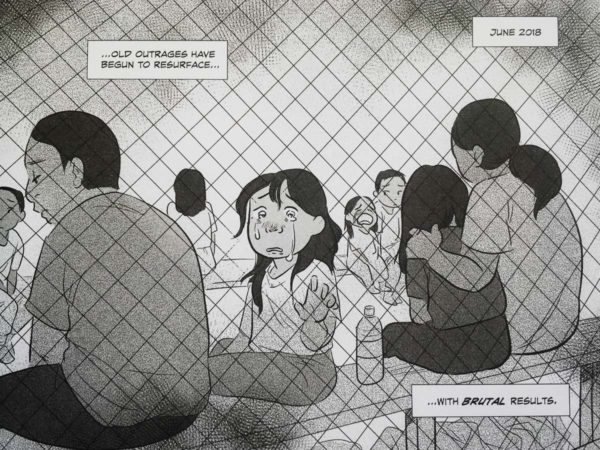

[Image: Panel from They Called Us Enemy, by George Takei, illustrated by Harmony Becker. A young child looks at us through a wire fence, fingers resting on the links, tears streaming from their eyes. Behind them, families and individuals sit hunched, some crying. Text overlay reads “June 2018 / …old outrages have begun to resurface…with brutal results.”]

Never again – You can do more than read a book

- Learn how to de-escalate anti-Asian harassment

- Register for free de-escalation & self-care trainings to survive when you find yourself the target of anti-Asian harassment.

- Or register for free online bystander intervention training for non-Asian allies & accomplices. Hosted by Asian Americans Advancing Justice | AAJC & Hollaback!

- Contact your senator

- Call for support on legislation like S. 2113, the Stop Cruelty to Migrant Children Act. Very easy to do with free Resistbot texts.

- Help reunite migrant families separated at the border

You may also like

- Japanese Internment Books for Kids & My Family’s Story via Mia Wenjen, #OwnVoices Japanese American kidlit critic

- Don’t Yuck My Yum: Delicious Kids Books That Dismantle Anti-Asian Racism

- How We Reinforce The Model Myth with Polar Bear Island

- #OwnVoices American Asian & Pacific Islander Kidlit Authors & Illustrators

- More Children’s Books about Japanese American Internment

- Anti-Racism For Kids 101: Starting To Talk About Race

- Kids Books on Solidarity, Allyship & Accomplices

- Kids stories that reinforce the white savior narrative

- How We Maintain Oppression With Kids Stories About Victims & Saviors (for members of our community who help me keep all the stuff above free)

Stay Curious, Stand Brave & Center Asian Voices

Support these resources via Paypal | Venmo | Ko-fi | Buy a t-shirt | Buy a book

Created Jan 30, 2017, last expanded with additional books & how this topic connects with current events in Jan 2021