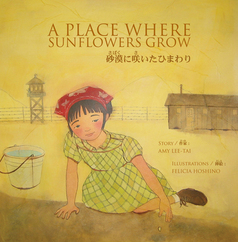

Sharing this post on social media? Use this description to make it accessible: [Image description: Cover of ‘Mup’ by Raea Gragg. A teen and young child submerged under water, both are illustrated as Black-presenting with green eyes and flowing dark brown hair”]

Mup

Raea Gragg

Graphic Novel, Not recommended

Keep Raising Luminaries & Books for Littles free and accessible for readers who can’t afford a paywall.

Posts may contain affiliate links, which allow me to earn a commission at no extra cost to you. Check out the full affiliate disclosure along with my statement of accountability. If you’re into supporting libraries (please do!) more than consumerism, you can also support my work directly:

Donate or shop using an affiliate link via| Paypal | Venmo | Ko-fi | Buy a t-shirt | Buy a book

For critical discussion with kids

Q (age 9) enjoyed the time travel, adventure, message against climate-devastating oil consumption and Mup’s character growth about self-identity as she approaches puberty. I did too!

HOWEVER. Controversy! There were many things we found problematic with this book. I went on a little rant about it that went far too long, so I’m just gonna sum it up into a few points and let you do your own digging.

It’s fine for kids to enjoy the goofy adventures created by white people unimpeded by racialized trauma. But for white readers in particular – this comes with the responsibility of recognizing bias, naming it, and committing to not replicating this harm.

You might also like: Kyriarchy-Smashing Books for 9-Year-Olds

Problematic: Brownface

This book was published in 2020. How on earth does a white lady not pause before writing a character based on her very white sister (that rich white girl slouch! That level-10 Patagonia-fleece whiteness!) and then paint her brown for no apparent reason other than a grab at the ‘diversity’ market?

Problematic: Tampering brownface with proximity of whiteness.

BIPOC have light eyes all the time, it’s normal!

The thing is they’re not any more or less acceptable or beautiful than those with darker coloring. Just in case Mup having flufflier hair and darker skin than white readers would be comfortable with, Graegg drew Mup with light skin and green eyes. How exotic! All the diversity points of brownface, with the subtle ‘but she’s pretty’ message that remind BIPOC that in white supremacy culture, fairer BIPOC are easier on the eyes, and easier to empathize with.

Problematic: Zero effort to embrace Mup’s appropriated Blackness beyond looks

In appropriating a Black-presenting character and implying she’s multiracial, the very least Graegg could have done was run this book past a Black reader to get notes on what she’s missing. Three girls with kinks and curls just plop bareheaded into sleeping bags and jump up in the morning like the world won’t take them seriously until they take that frizz. Imagine that life!

You might also like: No White Saviors: Kids Books About Black Women in US History

Problematic: ‘Gotcha’ language

Mup’s dad uses ‘then I got you’ to refer to the phenomena of obtaining Mup. Like she’s a freakin’ Pokemon. Or a token Black family member to prove he’s open-minded. Regardless of race and adoption status – it’s just weird and gross to talk to our kids like we collected them like pogs.

BIPOC who have been collected by a white person who preens over you as a prized element of their social collection, you know exactly what I’m talking about. This language wouldn’t be more than an awkward blip on the radar if it wasn’t a white dad talking to his multiracial / transracially adopted daughter. The implied backstory of adoption, breeding mixed babies to fix your racism, or even just that Warrior Parent nonsense of objectifying kids as catalysts for a parent’s heroic journey – Ick. Ew. Gross. No thank you.

You might also like: The Reality of Being Adopted: Validating Stories for Adopted Kids

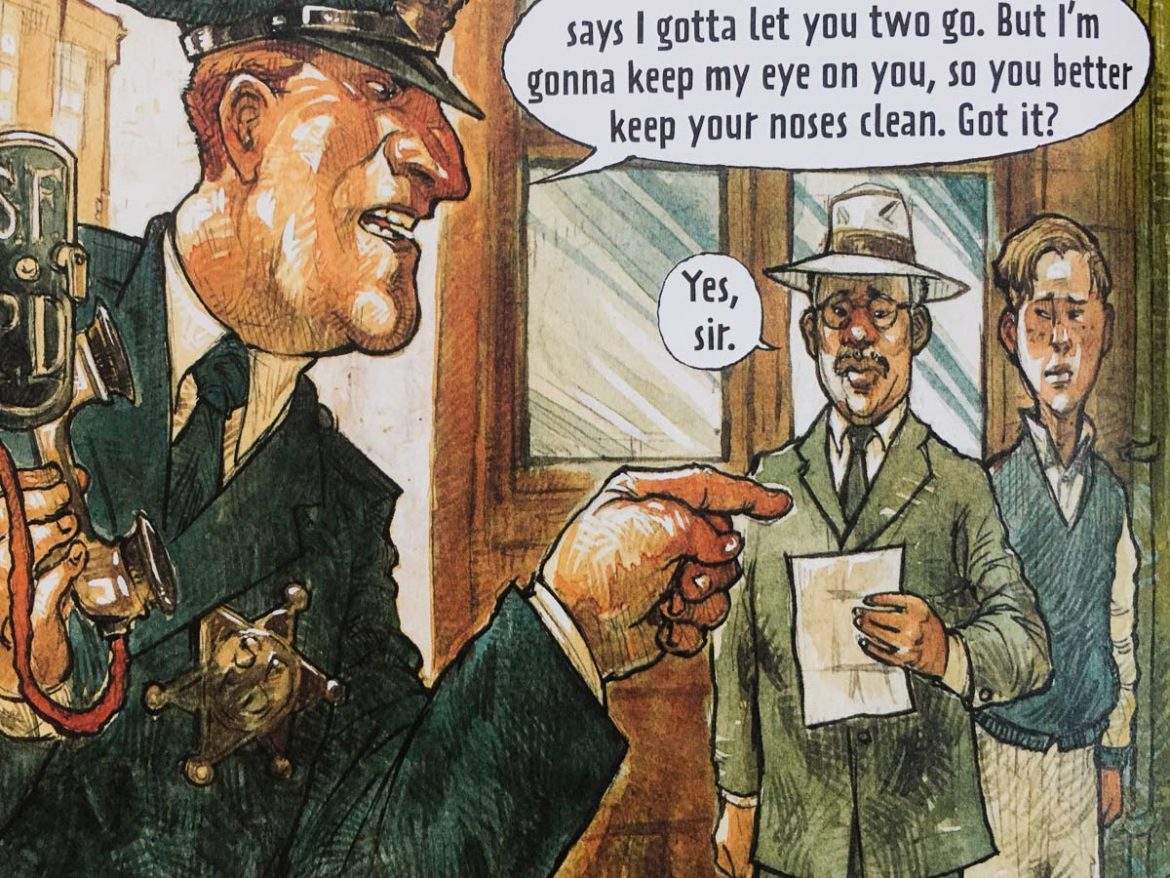

Problematic: Basic Boring Saviorism

The saviorism! A nameless, pan-African tribe has been invaded, colonized, and exploited by a white dude sporting a crown. It’s destroyed their way of life! They are helpless to stop it! Until two Americans show up and save the day within 48 hours.

You might also like: Creating An Anti-Racist Family Manifesto

OH COME THE FUCK ON, ALREADY: Complete lack of self-awareness

Alone, the nebulous, inky, infesting Black Dread (a creeping infestation that pollutes all life that is good and pure on Earth) would be a subtle sign that the author is not at all concerned with our culture’s value on lightness, whiteness, purity culture, and how it forms early bias and racial supremacy on young readers. But capitalizing on a shortcut based in anti-darkness while wearing the face of a Black-presenting character? On top of all the other goof in this book? Yikes.

Like the increased popularity of zombie movies during a refugee crisis and immigration boom, the symbolism of darkness as invading death takes on a deeper tone in the context of a white woman cherry-picking the symbolism of darkness to suit her whims.

Goodness gracious. What. WHAT. I mean we all make mistakes and goof up, cause harm, spread nonsense – but this is a hot messy lasagna of unapologetic privilege and zero self-awareness.

You might also like: Captivating Kids Stories To Recognize Privilege

Parenting is Praxis:

These conversations have to go somewhere. We can’t just read a book for ‘awareness’ and consider our work done. Here are a few ways we transform our family discussions from Freedom, We Sing into action:

- Talk about your family’s racial identities and recognize your role in working toward Black futures.

- Join & amplify the work of Revolutionary Humans, supporting social justice in parenting, non-profits, and community action.

- Find your local black-led organizations, check out the resources they suggest, and follow their lead in action.

You might also like: All My Sons Deserve Respect! Complex Black Boys In Kidlit

If you don’t have patience for this nonsense,

Grab some good graphic novels for elementary-aged kids

Additional Reading For Grownups:

- When They Call You A Terrorist: A Black Lives Matter Memoir

- Mindful of Race

- All My Sons Deserve Respect: Search for Complex Black Boys in Kidlit

You might also like: Children’s Books By Brilliant Black Women: #OwnVoices Authors & Illustrators

Is this #OwnVoices?

AHhahahah NO.

Learn more about #OwnVoices, coined by autistic author Corinne Duyvis

How we calculate the overall awesomeness score of books.

Stay Curious, Stand Brave, and Smash The Kyriarchy

Support the Abolitionist Youth Organizing Institute. My kids have two parents to support them – but through the AYOI, we can support and connect with youth to end targeted policing and incarceration.

“Project NIA [the AYOI lead organizer]’s mission is to dramatically reduce the reliance on arrest, detention, and incarceration for addressing youth crime and to instead promote the use of restorative and transformative practices, a concept that relies on community-based alternatives.

If my work makes it easier for you to raise kind & courageous kiddos, you can keep these resources free for everybody by sharing this post with your friends and reciprocate by supporting my work directly.

Ways to support Raising Luminaries: Paypal | Venmo | Ko-fi | Buy a t-shirt | Buy a book | Buy toothpaste | Subscribe to Little Feminist Book Club